Tết Nguyên Đán (Traditional Lunar New Year) is the biggest among traditional festivals for the Vietnamese people. Today, many ancient customs are still practised in the former royal capital. Many people ask the same question: How was the Lunar New Year organised by the Nguyễn kings in the past?

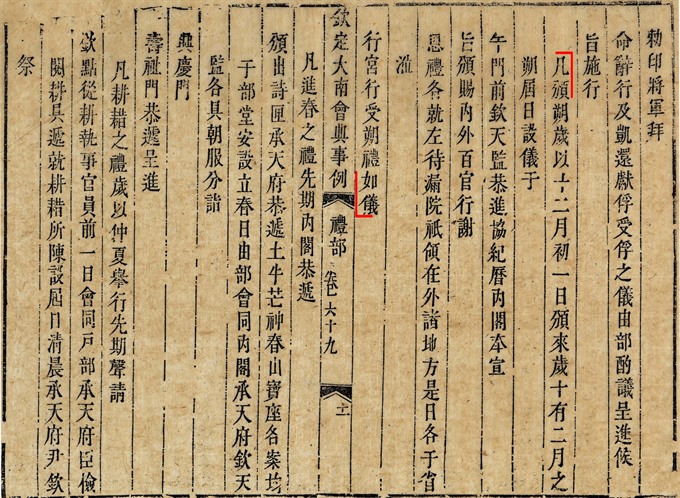

A printing block mentions ancient customs practised by the Nguyễn dynasty during the Lunar New Year holiday. Photo from the National Archives Centre No 4

There is a rare source of material that mentions the customs – the wood printing blocks from the Nguyễn dynasty (1802-1945), which have been kept at the National Archives Centre No 4. The blocks contain details on traditional customs practised for the Lunar New Year. The preparation work starts months before Tết.

On the first day of the last lunar month, Nguyễn kings organised the Ban Sóc ceremony to distribute calendars for royal mandarins at Ngọ Môn (Noon Gate). Ordinary people received calendar in their localities. At the same time, kings fixed the holidays for the Lunar New Year. After announcing the holiday, the royal family would decorate the royal palaces with parallel sentences, flags, flowers and lanterns. The holiday atmosphere began from that day.

A bamboo pole was erected at Huế royal complex in 2017. Photo thuathienhue.gov.vn

In the middle of the last lunar month, often on the 20th day (of the last lunar month), the royal family would organise the Phất Thức (Cleaning up) ceremony. At Cần Chánh Palace, there were six wooded wardrobes to store the royal seals. Servants would go to get water from the junction on Hương River and put flowers on the water. The seals would be cleaned with water scented with flowers and dried with a red cloth. The seals were then put back into the wardrobes, which were locked and sealed with a paper with letters: “Royal Seal”. After the event, mandarins and the king would be off work and did not use the seals. Only after a Khai Ấn (Seal Opening) ceremony at the beginning of the new lunar year would the seals be used again.

Two days later (on the 22nd day of the last lunar month), the king would come to Thái Miếu or Thế Miếu to host the Cáp Hưởng ceremony to invite late ancestors to return to royal palaces and enjoy Tết.

According to the book titled Khâm Định Đại Nam Hội Điển Sự Lệ, which lists regular events in the court, in the year of Buffalo, Cat, Snake, Goat and Pig, the king would go to Thái Miếu. In the year of Rat, Rooster, Dragon, Horse, Monkey and Dog, the king would go to Thế Miếu. From that day, the king ordered mandarins and princes to conduct worship ceremonies on behalf of the king at mausoleums, temples and pagodas around the royal citadel.

The last day of the lunar year might have been the most anticipated day. Early in the morning, princes and mandarins would disperse to temples to host the Tuế Trừ (Farewell to the Old Year) ceremony. The ceremony should be early in the morning, after which a cây nêu (a tall bamboo pole) was erected by the court.

The bamboo pole was stripped of its leaves, except for a tuft at the top. Bows, arrows, bells, gongs and other leaves to ward off evil spirits were hung on the tree with the hope that the bad luck of the previous year will be chased away and everyone has a happy New Year. Erecting the bamboo pole is a special ceremony at the threshold of the new year. When the pole of the king was erected at Thái Hòa Palace, bamboo poles in other palaces, pagodas were then erected.

The king directed the erection of the bamboo pole at Thái Hòa Palace, while princes and mandarins took care of the bamboo poles at pagodas and temples around the citadel.

That night, after organising Trừ Tịch ceremony to get rid of evil and bad lucks of the old year to welcome good luck for the new year, the whole citadel would light firecrackers hung on the bamboo poles.

The Nguyễn kings placed a lot of value in cultural traditions. File Photo

The bonus for tết was a crucial act by the Nguyễn kings, through which the kings encouraged their mandarins and servants.

Yet the bonus was given in a solemn ceremony on the first day of the lunar new year. Depending on conditions each year, the king might decide to give different objects as a bonus.

According to the book titled Khâm Định Đại Nam Hội Điển Sử Lệ (Historical Regular Events of Việt Nam), the bonus ceremony started in 1808, under King Gia Long (1802-1820). However, as the economy was not good, the bonus to mandarins was not mentioned.

King Minh Mạng (1820-1841) chose the way to host a royal party to entertain mandarins and gave them some money. King Thiệu Trị (1841-1847) gave mandarins letters as a gift. King Tự Đức (1847-1883) gave poems to mandarins. For the Lunar New Year in 1848, King Tự Đức composed a poem, gave it to mandarins to read and ordered it given as a gift to every mandarin and servant.

At the party to entertain the mandarins, the king said: “I want the king and servants to be close to one another like a human body, like father and son. All mandarins should not try to work only for the bonus and be scared only when punished.”

Nguyễn kings believed that a bonus on the Lunar New Year would enhance trust among royal members, bringing spiritual strength for the court.

The first year was welcomed differently by different kings. King Gia Long would go to Thái Miếu first and host a solemn worship ceremony. Then he would come to Thái Hòa Palace to host the Khánh Hạ ceremony, to have the first party with mandarins and give them bonus money.

Ancient folk games for the Lunar New Year at Huế citadel have been reorganised in recent years. Photo tienphong.vn

Under Tự Đức, he would come first to his mother’s palace and dedicate her gold, silver and best wishes for the new year. Then he would go to Văn Minh Palace to have tea with his mandarins. The second day of the new year, he continued to host parties, giving money and gold to mandarins.

Under King Kiến Phúc’s reign (only 8 months, Dec 1883- July 1884), the second day was his birthday so he wore his best royal coat and stayed at Văn Minh Palace. Mandarins would put on their best clothes like on the first day (of the Lunar New Year) to come to say happy birthday to the king.

On the third day, Nguyễn kings would host a party to say goodbye to the souls of late ancestors after they returned home to enjoy Tết with the living royal family. Various kinds of incense and votive papers were burned to send to Gods and holy spirits.

On the 7th day, the final day of the festival, the court and residents in the citadel organised a ceremony to take down the bamboo poles, ending the holiday. On the same day, mandarins caring for the royal seals hosted the Khai Ấn (Opening Seal) ceremony to start a new working year.

People can see that Nguyễn kings did not think of material enjoyment as important. They tended to care much more for cultural traditions.

Looking at the customs that Huế people practise during Tết, we can find similarities with those by the kings in the past.

Traditions are still kept alive by each Huế family and each home throughout the country. — VNS