PwC’s 2022 Workforce Hopes & Fears survey shows that there is an imbalance between available resources and a new and rapidly evolving workforce. Of nearly 18,000 employees based in Asia-Pacific who participated in the survey, one-third said that their territory lacks people with the skills to do their job, while 42 per cent are worried their employer will not teach them the technical or digital skills they need.

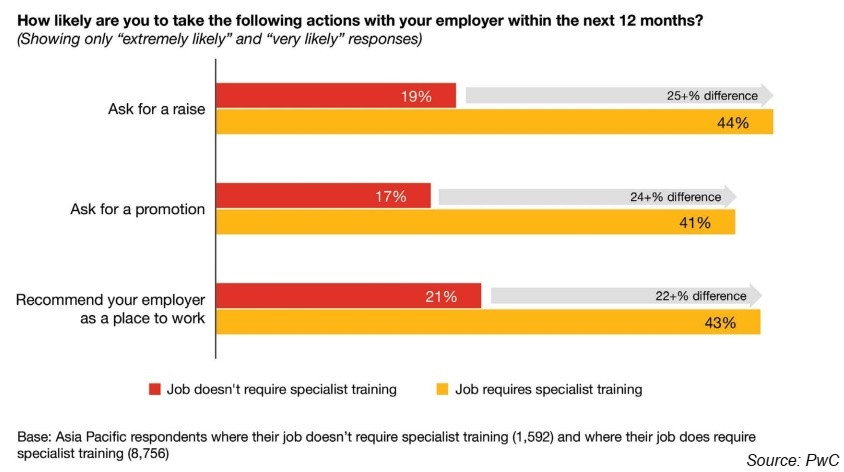

On the other hand, employees with specialisations are in high demand. “These empower workers by giving them more confidence and bargaining power. Skilled workers are at a distinct advantage in Asia-Pacific, where the skills shortage is particularly acute,” the report suggested.

Despite the skills shortages, less than half of employers are spending the necessary time and resources to upskill their workers. “Too often, companies see upskilling as a short-term fix for plugging immediate skills gaps rather than a way to develop a strategically competitive workforce,” the report assessed.

In Vietnam, the local workforce demonstrates a strong appetite for learning. About 84 per cent of respondents would learn new skills or completely re-train in order to improve future employability, much higher than the global responses’ level of 77 per cent. A strong 93 per cent are currently learning new skills, with the majority of these respondents saying that they are learning independently.

In addition, with millennials and Gen-Z gradually taking up a bigger portion of the labour force, a new approach to training is in dire need. According to the report, Gen-Z is the least content generation with their employment, while almost half of millennials fear their job would soon be replaced by new technology.

“One of the most important takeaways of our report is the focus on upskilling investment, not only in short-term campaign but comprehensive strategies that would bring lasting benefits,” said La Tran Minh, senior manager at PwC’s Workforce Transformation. “Employers need to identify the skills and knowledge that would be in demand in the next 5-10 years, in other words, to have long-term vision rather than short-term solutions.”

This specific demand for learning and education aligns with the country’s focus on digital transformation in the context of globalisation. As the World Bank suggested in its report Taking Stock: Educate to Grow published in August, the economy is moving from being driven by low-skill and low-wage jobs in manufacturing and services towards a more innovation-driven growth model built on higher value-added industries and services. Due to this, Vietnam will need a skilled workforce to transform itself into an upper-middle-income economy by 2035.

A deeper vision

Certain industries are getting ready for waves of tech and digitalisation that may affect employability. According to Vu Duc Chinh, director of the Department of Accounting and Auditing Regulations at the Ministry of Finance, finance and accounting are among the industries that are in transformation.

“In modern times, with robotic ‘colleagues’ who operate with high accuracy and zero demand for salary raise and promotion, any inadequacy in skills and knowledge poses a greater disadvantage for normal workers,” Chinh said. “Especially with the compulsory application of the IFRS accounting standards, the need for IT and computational fluency is amplified. And since the national adoption of IFRS requires a unified roadmap, one entity’s readiness in related training and upskilling may affect the whole system.”

However, Chinh suggested that the lack of appropriate skills has forced the industry to look at education with a more comprehensive vision. “Practical integration between workers’ skills and tech should start from the school level, as accountants with professional knowledge often lack computer skills and vice versa,” Chinh said. “Every individual should be able to look at the big picture and see what kind of training they need to fit in.”

Meanwhile, tech companies are facing their own challenges. Thao Pham, head of talent management, learning, and organisation development at VNG Corporation, said the key is to train the ability to adapt, not the knowledge itself.

“In this industry, however well-prepared you are in schools, it is almost impossible to catch up with new innovations that are happening on a daily basis,” Thao said. “While employees are expected to be able to manage change and ambiguity, corporations themselves need to be quick to react and adjust.”

|

| In Vietnam, high-skilled workers only comprise about 10-15 per cent of the workforce |

Tackling digital issues

In addition, while comprising mostly young workers who are tech-savvy and eager to learn, agility and resilience are also critical pieces of the puzzle for tech companies.

“About 98 per cent of our workforce are millennials and Gen-Z, who, as the report pointed out, are always keen on exploring the next new things. Hence, we often find that the mentoring and coaching approach is more effective than one-size-fits-all methods,” Pham added.

Organisations catering to the training and upskilling needs are seeing an increase in demand in the past five years. Cyberkid, a social enterprise aiming to tackle cybersecurity issues and train digital citizens from a young age, is also branching out on a platform which enables businesses to invest in relevant projects and recruit talents in tech. “Research shows that as machine learning evolves, the medium-skilled workforce is the group that’s most likely to be replaced. In Vietnam, high-skilled workers only comprise about 10-15 per cent of the workforce,” said Quynh Nguyen Nhu, CEO of Cyberkid Vietnam.

Consulting firms in Vietnam are also testing the water in the training area. PwC Vietnam last week launched the PwC Academy, a specialised external training arm, providing customised solutions and public workshops. Similarly, KPMG has its own segment called Private Enterprise, catering specifically to service the requirements of startups and emerging businesses.

Source: VIR