During the past fortnight South Africa has seen a dramatic, and unexpected slow-down in the daily rate of coronavirus infections.

Health experts are warning that it is far too early to see this as a significant development, and worry that it could even trigger a dangerous sense of complacency.

President Cyril Ramaphosa has now suggested that the two weeks of lockdown is responsible. He has extended the nationwide restrictiions, scheduled to end in one week's time, to the end of the month.

But - as the country and the continent continue to brace for the potentially devastating impact of the pandemic - doctors are struggling to explain what's going on.

The beds are ready. Wards have been cleared. Non-emergency operations rescheduled. Ambulances kitted out. Medical teams have been rehearsing non-stop for weeks. Managers have spent long hours in online meetings drawing up, and tweaking their emergency plans.

But so far, and against most predictions, South Africa's hospitals remain quiet, the anticipated "tsunami" of infections that many experts here have been waiting for has yet to materialise.

"It's a bit strange. Eerie. No-one is sure what to make of it," said Dr Evan Shoul, an infectious disease specialist in the main city, Johannesburg.

"We're a bit perplexed," said Dr Tom Boyles, another infectious disease doctor at Johannesburg's Helen Joseph Hospital, one of the biggest public hospitals in the city.

"We've been calling it the calm before the storm for about three weeks. We're getting everything set up here. And it just hasn't arrived. It's weird."

Aggressive tracing of contacts

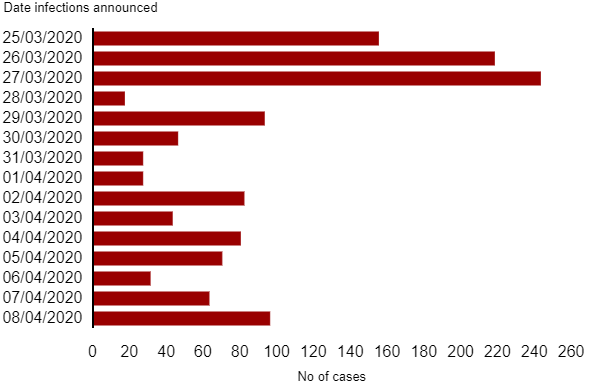

It is nearly five weeks since the first confirmed Covid-19 case in South Africa, and until 28 March, the daily graph tracking the number of new infections followed a familiar, accelerating, upward curve.

But on that Saturday, the curve suddenly broke sharply - from 243 new cases in one day, to just 17. Since then, the daily average has settled at around 50 new cases.

Could it be that South Africa's early, and strict lockdown, and its aggressive tracing work, are actually working? Or is this just a small lull?

On Thursday President Ramaphosa said it was "too early to make a definite analysis", but he said that since the lockdown had been introduced the daily increase in infections had dropped from 42% to "around 4%".

"I think the more people we test, the more we'll reveal whether it's an aberration, or it's real. The numbers are not yet there," cautioned Precious Matotso, a public health official who is monitoring South Africa's pandemic on behalf of the World Health Organization (WHO).

Complacency fears

There is a general acknowledgement here, from the health minister to frontline hospital staff, that it is dangerously early to try to reach any firm conclusions about the spread of the virus.

"It's difficult to predict which road we're going to take - a high, middle or low [rate of infection]. We don't have widespread testing.

"There might be early signs that are positive, but my fear is that people start becoming complacent, based on limited data," said Stavros Nicolaou, a healthcare executive now coordinating elements of the private sector's response.

The sense of a vacuum caused by this extended lull - the potential "calm before a devastating storm," as Health Minister Zweli Mkhize described it last week - is, inevitably, being filled by speculation.

The widespread assumption has been that the virus - introduced to South Africa, and many other African countries largely by wealthier travellers and foreign visitors - would inevitably move into poorer, crowded neighbourhoods and spread fast.

Nervous anticipation

According to experts, that remains the most likely next stage of the outbreak, and there have already been several confirmed infections in a number of townships.

But doctors here and in some neighbouring countries have noted that public hospitals have seen not yet any hint of an increase in admissions for respiratory infections - the most likely indication that, despite limited testing, the virus is spreading fast.

One theory is that South Africans might have extra protection against the virus because of a variety of possible medical factors - ranging from the compulsory anti-tuberculosis BCG vaccine that almost all citizens here are given at birth, to the potential impact of anti-retroviral HIV medication, to the possible role of different enzymes in different population groups.

But these ideas have not been verified.

"These stories have been around for a while. I'd be amazed if it was BCG. These are theories. They're probably not true," said Dr Boyles.

"It's an interesting hypothesis" but nothing more than that, said Prof Salim Karim, South Africa's leading HIV expert, of the BCG jab. He chided "instant experts" for promoting unverified solutions on social media.

|

|

Confirmed coronavirus cases in South Africa |

"I don't think anyone on the planet has got the answers," said Mr Nicolaou.

"We're still planning as if the tsunami is coming. The feeling is still very much one of great nervous anticipation," said Dr Shoul.

And so South Africa waits - wondering whether it is experiencing a minor pause before what one doctor here called "an intergalactic spike," or something more significant.

The more important question may be whether these quiet weeks are being put to good use.

There have been particular concerns that the state health system has been slow to implement an aggressive testing regime and is currently too dependent on private clinics.

Internal health department correspondence, seen by the BBC, points to growing concerns about mismanagement and dysfunction within the state system, particularly regarding the slow rate of testing.

But those concerns are balanced by growing confidence in the government's "evidence-based" approach to the pandemic, and by encouraging signs of increasingly constructive and formal cooperation between the state and the private sector. BBC